The Bright Side of Leprosy

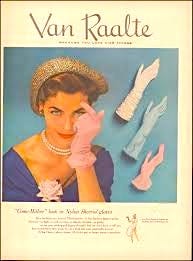

Fancy New Gloves!

When I told my mother about my diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease at age 49, I half expected her to cheer.

“Excellent news!” she might say. “You and your incredible luck! Time to buy a lottery ticket.”

Of course, my milk and honey of a mama would neither say nor think anything of the sort. She would be devastated, but I would never know that. She would take me by the arm to skip through the splashy streets of Singing in the Rain, hugging slippery light poles and tap dancing in puddles while we tour the magical land of Parkinsonia - Where Tremors Just Make for Better Jazz Hands.

Forty-nine years into a relationship with my mom, I knew there was no news bad enough that she couldn’t find some way to forge a happy ending; She listens, she consoles, she sends cookies next-day air, but to her there is no such thing as defeat.

If mom had Leprosy, she would immediately declare in the most chipper of tones that the diagnosis was just the opportunity she had been waiting for to buy some fancy new gloves! Her first internet search would not be “How long do I have until my arms fall off?”, but “Does Bergdorf's carry gloves?” She would learn the difference between goatskin gloves and calfskin gloves and know which gloves to use for what occasions. She would learn that the French word for someone who makes gloves is a gantier and fly (first class, of course) under cover of darkness to the most famous gantier in all of France.

And, most importantly, she would tell no one. My mom would quietly buzz about wearing her gloves as if she had always worn them around all day every day. To her law firm, to the taco place around the corner from our house, to the grocery store, and to the opera.

“Who doesn't wear gloves to the opera?”

Nothing to see here. Keep moving.

My mother is a make breakfast, coffee-to-go, bazooka the glass ceiling before lunch kind of gal. A put on some lipstick, spritz on some perfume, and get back out there tough. The world depends on you, don't let them down.

I’ve asked my inhumanly resilient mom many times before when I knew she wasn’t feeling well, “don’t you want to complain just a little bit?”

“No.”

“Don’t you want to spend at least a day or two stomping around and swearing at the sky?”

Again, no. Her loss.

Unlike my mom, I need a minute, a day or even maybe a year. I tend to soak in a luxuriously familiar tub of discomfort until my hands prune and I can watch the milky bubbles pop around the silver drain. And there I will sit in an empty vessel with tears streaming down my face until I am ready to get up and begin again.

There is no sleight-of-hand “look over there!” trick to dissolve the molten gruesomeness of a Parkinson’s Disease decline. This is no temporary financial hiccup she could solve with a quick bank transfer or some other mess of mine that she could untangle with a call or two. This is a well-described scientifically studied disease with a predictable pattern of descent.

On January 27, 2020, at my youngest son’s 10th birthday dinner, I hid my face behind the menu and whispered quietly to my mother sitting next to me, “I have Parkinson’s disease.” I had just learned of it that morning and didn’t want to ruin my sweet boy’s special moment, but I couldn’t hold it in any longer. Tears poured out of my eyes and down my cheeks.

Even a grown woman still needs her mom sometimes. For my whole life, every single failure I have ever had, my mom has wiped my tears, brushed off my knees and pushed me to keep moving. This time would have to be different. This was unfixable.

Everyone breaks. Some of us heal quickly and some of us never heal at all. This was my first glimpse of never at all.

In some upside down way, telling my mother I had an incurable brain disease felt like a victory of sorts. I had her backed into a corner. She had to declare defeat and admit, for the first time ever, that I was indeed doomed.

Over the next few months, my mom and I had the same conversation on repeat.

“You will be okay,” she said.

“Mom, I have an incurable neurological disease. I will not be okay. Please stop saying it will be okay when it won’t. It literally, by definition, will not be okay.”

“Science is remarkable. This will not be as bad as you think.”

We were side-by-side in the same movie theater watching completely different movies.

When I lay hiding in my closet on a pile of dirty clothes sobbing into the phone to her, some part of me wanted to hear from her that yes, my life would not be what I thought it was going to be. That was what I saw on the screen, and I wanted her to see it too. I needed her to see it. What about the word “incurable” did my mom not understand? I wanted to hear that she was sorry that I was going to die a slow and miserable death. I wanted to hear that she knew that it wasn’t fair and that I didn’t deserve this fate. How could we even begin the conversation about a topic when one of us was pretending to not exist?

There is no bright line marking the territory between resilience and toxic positivity. There are no file folders in the office supply store marked, “Mind-Blowingly Out of Touch With What is Actually Happening” and “This Sucks and I’m Sorry” to choose between.

In my 54 years of life, I have spent a lot of time trying to discern why my mom’s invisible force field seems so impenetrable to the bad things that happen and mine is so vulnerable to them. I used to joke about the reality of life saying that “someone is going to punch me in the face today, I just don’t know who will do it and when.” What a terrible message to be repeating to myself over and over. Even in jest.

And then, it finally clicked for me.

My mom isn’t ignoring the facts. She is accepting them. Instantaneously. She isn’t fighting anything; she has already decided how she will respond to a particular set of facts before they’ve even materialized. Every second she spends pouting or stomping around is a lost second of life. Seconds add up to minutes that add up to days that add up to years.

What my mom is trying to tell me when she’s refusing to entertain the conversation about my potential deterioration is that she’s refusing to let me miss even one second of this beautiful life that is in front of me right now. Ruminating on my impending doom and being present are mutually exclusive. I have a choice I can make. How do I want to spend those seconds, days, and years?

What I’ve finally come to understand is the choice I have with the facts I am given.

How we respond doesn’t change the facts. Being optimistic in the face of bad news is not toxic positivity. It’s resilience.

Now, where do I order hot pink calfskin gloves?